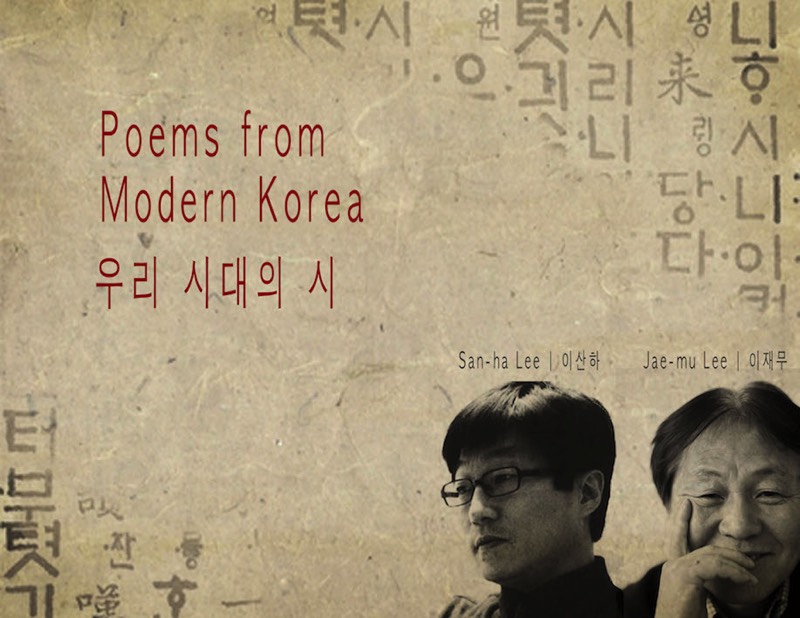

photos of San-ha Lee & Jae-mu Lee © 강세철 | 오병돈

Courtesy of www.koreanlit.com © Korean Cultural Service of Massachusetts

Commentary by Heeju Yoo | 유희주

Poet, President of Korean cultural service of Massachusetts

우리 Koreanlit.com에서는 여러 시인의 시를 번역했는데 보스톤의 한인 교회에서 한국 문화제를 개최할 때 낭송하고 싶다고 전한 두 시인의 시 (이산하-나무, 대나무 이재무-내가 시골길에서 넘어지는 이유, 얼굴)를 보고는 깜짝 놀랐습니다. 두 시인은 자신의 삶과 시를 명징하게 삶과 시에서 보여주는 몇 안 되는 시인들이기 때문입니다. 시를 보는 안목이 여간하지 않고서는 짧은 시에 내포되어 있는 메타포를 읽어내기가 쉽지 않은 시였기 때문입니다.

이산하 시인은 한국의 자주적인 국가를 위해 자신의 삶을 던진 사람으로서 그의 청춘과 삶은 송두리째 고립된 시간 속에 있었습니다. [나무]라는 시에서 -나를 찍으면 그 도끼날에 향기를 묻혀 주겠다-고 한 짧은 시는 완전히 시인의 삶 다운 시입니다.

이재무 시인 또한 대쪽같은 성품으로 속엣말을 담아두지 못하는 시인입니다. 그러나 그는 울퉁불퉁한 시골길을 사람이 그리워 심장이 두근거리는 것으로 읽어내고 기꺼이 그 길 위에 넘어져 주.는. 마음을 보입니다.

짧지만 가볍게 읽을 수 없는 시, 여러 번 읽어야만 하는 시를 한국인과 미국인들에게 소개하게 되어 기쁩니다. 번역은 보스턴 칼리지에서 한국어를 가르치시는 전승희 교수님이 하셨습니다.

Koreanlit.com 에 가셔서 시의 전문을 보시기 바랍니다.

We, at the koreanlit.com, have translated works by many poets, and when the Korean Church of Boston requested permission to use two poets in particular, their choices surprised us. These two poets are among the precious few who reveal their own life and truths as pithily as the nail penetrates wood. It seems the organizers meant business in mining for metaphors hiding behind brevity of the pieces.

The poet San-ha Lee dedicated his whole life for an autonomous Korea, sacrificing his youthful years stranded in total isolation. When he says, in the poem "Tree," that "(he will smear) A lingering fragrance / On the edge of your axe," it is true to his own life itself.

Jae-mu Lee, the other poet, is also a bamboo tree of a character - someone who cannot contain the words that need to come out. However, he reveals a generous heart upon stumbling over the rugged country road when he interprets it as if the forlorn road was longing for somebody to embrace.

These are poems of brevity yet also of lingering resonance. We are very pleased that they will now reach beyond the Korean readership. Their translation into English had been done by Professor Seung-Hee Jeon who teaches Korean at Boston College.

We hope you will go on to explore a more comprehensive body of work by the poets at www.koreanlit.com.

내가 시골길에서 넘어지는 이유

by Jae-mu Lee | 이재무

It thumps along too, like it missed human beings.

Now I know

Why I often stumble on a country road.

길도 두근두근 사람이 그리웠나보다

이제사 알겠다

내가 시골길에서 자주 넘어지는 이유를

by San-ha Lee | 이산하

Then I’ll smear

A lingering fragrance

On the edge of your axe.

그럼 난

네 도끼날에

향기를 묻혀주마.

by Jae-mu Lee | 이재무

Like a fan on a hot day,

Like a stove on a cold day.

It ripples while smiling,

It furrows while laughing.

Strong against wind,

Weak against water, like window paper.

Desolate

Like the ceiling of a moonlit room.

Like the afternoon mountain shadow in the backyard,

Like scriptures hand-copied in a notebook.

더운 날 부채 같은

추운 날 난로 같은

미소에 잔물결 일고

대소에 밭고랑 생기는

바람에 강하고

물에 약한 창호지 같은

달빛 스민 빈 방 천장 같은

뒤꼍에 고인 오후의 산그늘처럼

적막한

공책에 옮겨 쓴 경전 같은.

by San-ha Lee | 이산하

It becomes a spear.

If one end is bent slightly,

It becomes a hoe for weeding.

If holes are bored into its body,

It becomes a melodious flute.

If shaken by the wind,

It empties its insides to become stronger.

And, at last,

After blooming

Just once in 60 years,

It stops breathing.

I wish I could be like a bamboo.

날카로운 창이 되고

끝을 살짝 구부리면

밭을 매는 호미가 되고

몸통에 구멍을 뚫으면

아름다운 피리가 되고

바람 불어 흔들리면

안을 비워 더욱 단단해지고

그리하여

60년 만에 처음으로

단 한번 꽃을 피운 다음

숨을 딱 끊어버리는

그런 대나무가 되고 싶다.

Comments by DoYeon Kim, Music Director

The traditional piece accompanying the marriage ceremony is called Long Live for a Millennium | 천년만세 performed in the spirit of wishing the couple to live happily for a long time until their hairs become white and beyond. | 천년만세는 수명이 천년만년 이어지기를 기원하는 의미를 담고 있다. 신랑 신부가 천년만년 검은 머리 파뿌리 되도록 행복하게 살기를 기원하며 천년만세를 연주한다.

The Strangers is an original spin on one of the most popular folk music called "Bird Song" in Korea. Its verse describes a scene where all kinds of birds swarm in around the singer who praises their variety in exultation. gamin, the composer of this variation, thought of this community of people and cultures from all over the world. We are all immigrants one way or another, sometimes strangers to others but at the same time part of the harmonious whole (hopefully…?). 민요 새타령을 주제로 구성한 음악이다. 새타령의 가사 속에 여러종류의 새들이 날아드는 자연의 풍경을 노래하는 것에서 세계속의 다양한 민족과 문화를 생각하였다. 우리도 때로는 주인이 되기도 하고 이방인의 모습을 띄고 삶을 살아갈 수도 있듯이 다양한 사람들의 삶의 모습을 표현하고자 하였다.

Vagabond Voyage

From most of my life, I always have set a clear goal and try to achieve it, as achieving the goal made me feel alive. This summer I went sea-kayaking at the La Jolla Cove off the coast of San Diego. My goal was to reach the cave and come back, but when I looked out at the horizon, I realized how narrow my sight had been. I felt small and insignificant while I was captivated by the beauty of the vast ocean. How much of life I've been missing out on while I was set on such narrow and short-sighted goals! This piece grew out of that realization, partly with some regret, but also in the hopeful spirit.

Torn: Light and Darkness

When light comes into a dark room, it appears to dispel the darkness. However, the light is not able to fill the entire space. Instead, we see shadows and sunsets. In this composition, I explore the liminality between the light and the darkness.

Editorial Comments

The Hill Where the Tree Is | 나무가 있는 언덕

The composer of this piece, Hyungsun Ryu | 류형선 became a professional musician after hearing, as a high school student, the legendary underground protest songwriter Minki Kim | 김민기 from a bootlegged tape. After twenty years, he has garnered numerous accolades in various genres of Korean music that includes Traditional | 국악, classical | 클래식, Musicals, and CCM | 크리스찬 음악. Throughout his career, his primary interest has always been on the renewal of the Korean tradition via its creative fusion with the western classical music as well as attaining broader acceptance of its new style. He also wrote many pieces in the vein of progressive Christian music. He is also influenced by and wrote several pieces dedicated to the late Pastor and activist Moon Ik-Hwan | 문익환, one of the leading lights for the progressive movement in modern Korea. The piece performed for the concert is from the album "The Six-String Stepping Stone" | 여섯줄의 징검다리 which was a nominee for the Korean Music Award in 2009. ( source: Newsnjoy interview )

"Longing" - The Korean Art Song Tradition

The beginning of the Korean Art Song tradition goes back to around 1910 when the form was largely called "Chang-Ga". Its birth had been influenced by the arrival of the US Presbyterian Church and its effort to translate Christian hymns into Korean language. The first "Art Song" | 가곡 of Korea is largely attributed to the composer Nan-pa Hong | 홍난파 who composed "Garden Balsam" | 울밑에선 봉선화. The plaintive song became very popular as it sublimates the sentiment shared by most Koreans under the Japanese occupation. The subsequent development and refinement of the genre may be illustrated by the career of Youngsub Choi, one of the most famous composers (considered "Schubert of Korea" by some) of the form (whose "Mermories" is the last song in the segment). He was among the first to study abroad, in Austria and Germany, during the Korean War. Coming back home in 1954, he began to modernize the form, composed ambitious song-cycles, songs with orchestral accompaniment and large scale cantatas. Probably the most beloved song of his is "The Longing of Gumgang Mountains" | 그리운 금강산, composed in 1961 as part of a cantata commissioned by the Korean Broadcasting System. Initially set to the text that aligned with the strong hostility to North Korea (granted it was only a few years after the bloody war), its lyrics later went through changes reflecting the shifting political winds, sad reminder of the checkered trajectory of the mainstream Korean culture in the modern era as it charted censorships, political meddles, and even blacklisting that persisted to the very recent years.

The "Han" | 한 (loosely translated as Deep Sorrow or Lament) is often discussed as the representative of the pervasive Korean sentiment. This characterization may sound convincing given the relentless plights that pervade most of the Korean history. It may not be a coincidence that many of these Art Songs are themed around "Longing", the theme Youmi Cho (soprano) chose for the segment. "Unrequited ..." is the key word here whether it be about missing someone, hometown or the years gone by. Aside from the Art Song | 가곡 form, there of course is the parallel branch of the Korean Pop | 가요 that garners wider popularity. For younger generations both in and outside of Korea, either of these branches may impress as starkly distinct from a typical song by any of the current "K-Pop" groups. However, the nostalgic, the sentimental, and the sorrowful elements common to them all still appeal to the parental generation of, say, BTS members and their fans. If you are young and a diehard fan of ardent ballads put out by the K-Pop group du jour when they are not bouncing around the stage, it still merits to get acquainted with the root of their sweeter side.

The piri | 피리 is a cylindrical double-reed bamboo oboe with eight finger holes, one in the back for the thumb and seven in the front. Its’ large reed and cylindrical bore gives it a sound mellower than that of many other types of oboe. The piri is an essential instrument and popularly used in both folk and classical court music. There are other piris named hyang piri and dang (Tang) piri classified by the periods they were imported from China.

The saenghwang | 생황 is a Korean wind instrument. It is a free reed mouth organ derived from (and quite similar to) the Chinese sheng, though its’ tuning is different. It is constructed from 17 bamboo pipes, each with a metal free reed, mounted vertically in a windchest. Traditionally the saenghwang's windchest was made out of a dried gourd but nowadays it is more commonly made of metal or wood. In contrast to other Korean traditional instruments, it is not well known today, even in Korea, and very few musicians are able to play it. It is used primarily in chamber music, usually in combination with instruments such as the danso (vertical flute) and yanggeum (hammered dulcimer). The instrument was referred to historically as sang.

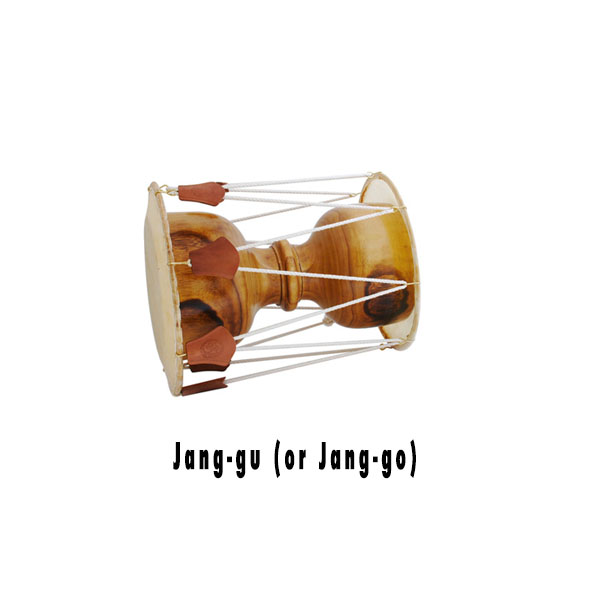

It is usually classified as an accompanying instrument because of its flexible nature and its agility with complex rhythms. The performer use his or her hands as well as sticks, producing various sounds and tempi, deep and full, soft and tender. Menacing sounds and fast and slow beats are also created to suit the mood of the audience. Using this capability, a dextrous performer can dance along moving his or her shoulders up and down and make the audience become carried away and dance along with him or her. (adapted from Wikipedia)